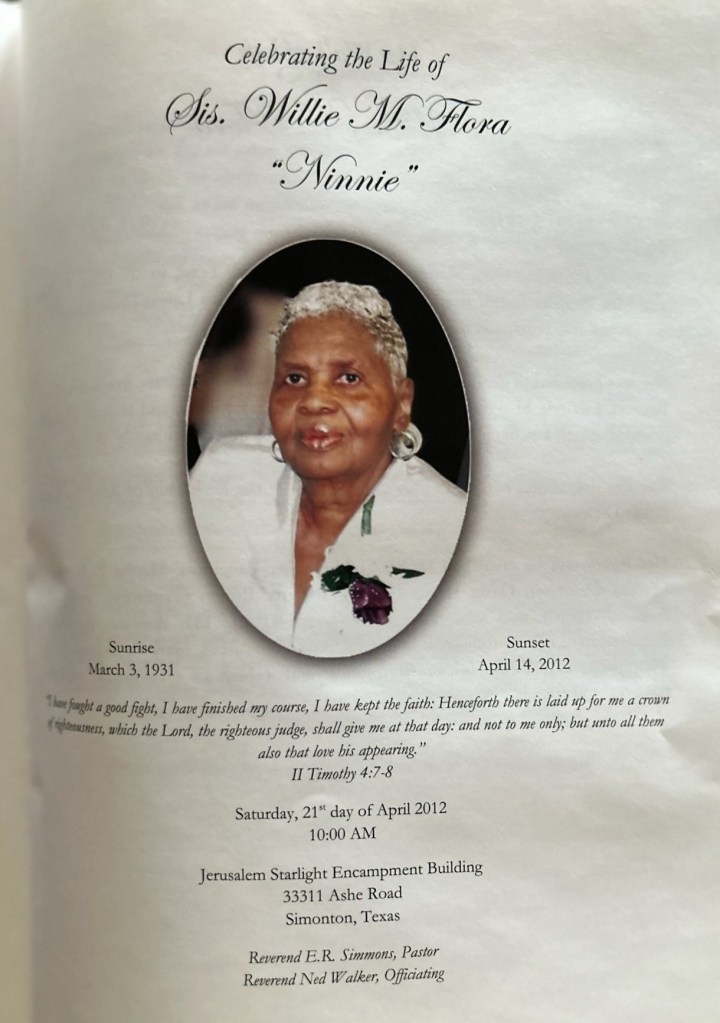

Groundbreaking research is currently being conducted in the medical field on treatment programs including new medicines for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In 2011 when I wrote this piece and published it for the first time, Pretty and I had become caregivers for my mother for the previous three years with the goals of keeping her safe and comfortable. We were told her dementia would get progressively worse with no hope for improvement. We saw that prognosis slowly come true. Last week Pretty’s ongoing work on bringing order to the very old boxes in her warehouse revealed a small black box containing my mother’s notebook prepared by the funeral home that took care of her final remains and resting place in 2012. Inside the notebook was her copy of my first book Deep in the Heart: A Memoir of Love and Longing that I gave her in 2007.

****************

August 08, 2011

Last week I visited my mother who is in a Memory Care Unit in a facility in Houston, Texas. She is eighty-three years old and has lived there for two years. She is a short, thin woman with severe scoliosis. Her curved spine makes walking difficult, but she shuffles along with the customary purpose and determination that characterized her entire life. Her silver hair looks much the same as it has for the last thirty years, missing only the rigidity it once had as a result of weekly trips to the beauty parlor and massive amounts of hairspray.

Her skin is extraordinarily free of wrinkles and typically covered with makeup. She wears the identical mismatched colors she wore on my last visit. Black blouse and blue pants. This is atypical for the prim, little woman for whom image was so important throughout her life and is indicative of the effect of her dementia.

My mother is a stubborn woman who wanted to control everyone and everything in her life because she grew up in a home ruled by poverty and loss and had no control over anything. Her father died when she was eleven years old. He left a family of four children and assorted business debts to a wife with no education past the third grade. Life wasn’t easy for the little girl and her three older brothers who were raised by a single mom in a rural east Texas town during the Great Depression.

My mom survived, married her childhood sweetheart, and had a daughter. The great passions of her life, which she shared with my father, were religion and education and me, possibly in that order. She played the piano in Southern Baptist churches for over sixty years. She taught elementary grades in three different Texas public schools for twenty-five years. The heart of the tragedies in her adult life made a complete circle and returned to losses similar to the ones she experienced in her childhood: her mother who fought and lost a battle with depression, two husbands who waged unsuccessful wars against cancer, an invalid brother who progressively demanded more care until his death, and a daughter whose sexual orientation defied the laws of her church. Alas, no grandchildren.

My sense is that my mother prefers the order of her life now to the chaos that confronted her when dementia began to overpower her. She knew she was losing control of everything, and she did not go gently into that good night. Today, she seems more content. At least, that’s my observation during my infrequent visits.

“My daughter lives a thousand miles from me,” she always announces to anyone who will listen. “She can’t stay long. She’s got to get back to work.”

We struggle to find things to talk about when I visit, and that isn’t merely a consequence of her condition. We’ve had a difficult relationship. Our happiest moments now are often the times we spend taking naps. She has a bed with a faded navy blue and white striped bedspread, a dark blue corduroy recliner at the foot of her bed, and one small wooden chair next to her desk. I sleep in the recliner, and she closes her eyes while she stretches out on the bed.

The room is quiet with occasional noises from other residents and staff in the hallway outside her door. They don’t disturb us. She has no interest in the television I thought was so important for her to take when I moved her into this place. I notice it is unplugged. Again.

“Lightning may strike,” she says when I ask her why she refuses to watch the TV in her room. “Besides, I like to watch the shows with the others on the big TV. Sometimes we watch Wheel of Fortune, and sometimes we watch a movie.”

I give up and close my eyes.

“I love this book,” my mother says, startling me awake with her words. I open my eyes to see her sitting across from me. She’s in the small wooden chair with the straight back. I can’t believe she’s holding the copy of my book, Deep in the Heart, which I gave her two years ago. I never saw the book since then in any of my visits, and I assumed she either threw it away or lost it. I was also stunned to see how worn it was. The only other book she had that I’d seen in that condition was The Holy Bible.

“I know all the people in this book,” she continues. “And many of the stories, too.”

“Yes, you do,” I agree. “The book is about our family.”

And, then, for the second time in as many weeks, I hear another reader say my words. My mother reads to me as she rarely did when I was a child. She was always too busy with the tasks of studying when she went to college, preparing for classes when she taught school, cooking, cleaning, ironing, practicing her music for Sunday and choir practice—she couldn’t sit still unless my dad insisted that she stop to catch her breath.

But, today, she reads to me. She laughs at the right moments and makes sure to read “with expression,” as the teacher in her remembers. Occasionally, she turns a page and already knows what the next words are. I’m amazed and moved. I have to fight the tears that could spoil the moment for us. I think of the costs of dishonesty on my part, and denial on hers for sixty-five years. The sense of loss is overwhelming.

The words connect us as she reads. For the first time in a very long while, we’re at ease with each other. Just the two of us in the little room with words that renew a connection severed by a distance not measured in miles. She chooses stories that are not about her or her daughter’s differences. That’s her prerogative, because she’s the reader.

She reads from a place deep within her that has refused to surrender these memories. When she tires, she closes the book and sits back in the chair.

“We’ll read some more later,” she says.

I lean closer to her.

“Yes, we will. It makes me so happy to know you like the book. It took me two years to write these stories, but I’m glad you enjoy them so much.”

“Two years,” she repeats. “You have a wonderful vocabulary.”

*******************

what Pretty found

You must be logged in to post a comment.