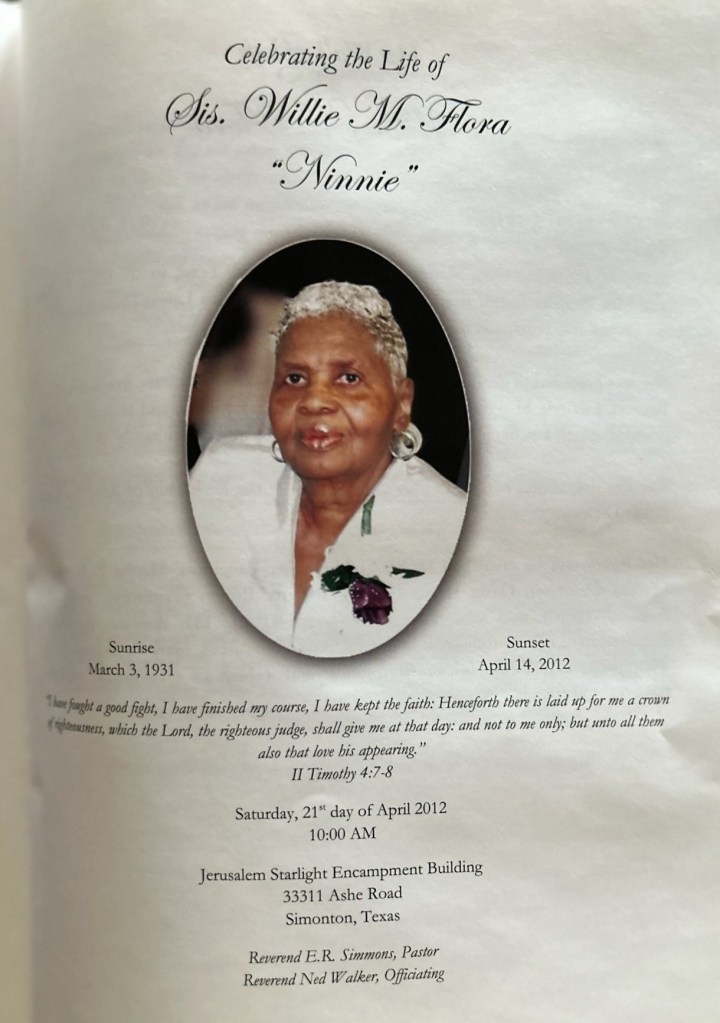

On my 66th. birthday I sat in a pew behind the family at a celebration of life in the Jerusalem Starlight Encampment Building in Simonton, Texas. It was my only visit to the church, and I was there to say goodbye to a Black woman who had been my best friend, like a second mother to me, for the previous forty-five years.

“Her legacy will be cherished by her five daughters, two sons, twenty-one grandchildren, twenty-four great-grandchildren, three nieces and a host of great-nieces, nephews, relatives and friends,” was part of the commentary on the life of a Black woman whose celebration of life took place on April 21, 2012, in the city of Simonton, Texas, which was located within the Houston metropolitan area.

Willie Meta “Ninnie” Robbins Flora wasn’t a famous public figure like Maya Angelou, not a political icon of the Civil Rights movement like Rosa Parks, not a household name like Shirley Chisholm – and yet her influence has been felt in the lives of ordinary people who were touched by her generosity of spirit, her keen sense of humor, and her loving care for those who needed help in any form. She has earned her place in Black History Month to me and others. Her niece Verna wrote a moving tribute to her Aunt Ninnie for the Celebration Program in 2012.

Aunt Ninnie was called many names, Skin, Cat Momma, Girlie, Aunt, Cousin, Sister, Road dog, Mother, but most of all she was called Mom. She was the type of person that, whatever you needed, no matter what it was, you had it. Now I guess you are wondering, “Why Road dog?” You see, my Auntie was my best friend. I remember when I was staying in Houston, I would call my Auntie every day and ask her what she was doing, and she would say,”Sitting on the side of the bed waiting on the next thing smoking.” We didn’t talk very much; we just enjoyed each other’s company. Man! We all loved her cooking! We couldn’t wait til Sunday, because that’s when we all met after church, and what a time we had! Auntie had something that everyone liked, because she wanted to make everyone happy. That’s the kind of person she was. Our loved one was no stranger to anyone. She was always there with a helping hand. I could go on and on about Mrs. Willie Flora. So Auntie, I’m waiting on the next thing smoking. See you on the other side. Rest in Peace, Love, Verna

*******************

Willie was in my life from the summer I graduated college in 1967 until her passing in 2012. As Verna said in her tribute above, she was always there with a helping hand to everyone – including me and my entire family.

I loved Willie Flora. She was wise with wisdom born of pain, but she turned her pain into a quick wit that laughed at herself and everyone she knew. She had spunk, and I admired her for standing tall – refusing to be defined by a world that often saw only the color of her skin.

I miss her to this day. I am waiting with her and Verna for the next thing smoking on the other side.

Sheila Rae

You must be logged in to post a comment.