Pardon the summertime interruption with this favorite story of mine from my days growing up in Texas. Yesterday was my grandfather the barber’s birthday. He was born July 29, 1898, and died in October, 1987. To me and my Morris first cousins, he was the best man we ever knew.

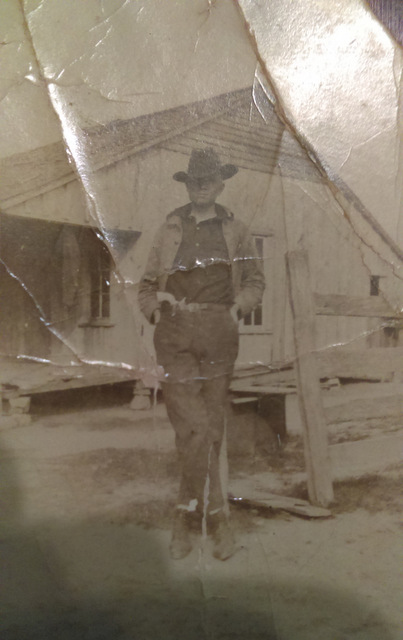

my grandfather, George Patton Morris, holding me in 1946

“George, here comes Sheila for her shave,” said Old Man Tom Grissom, who was already in his favorite spot in the barbershop by the time I got there.

Ma, my grandmother who had been married to Barber George Morris for over forty years, said Tom Grissom ought to pay rent for all the time he spent sitting on that bench in the shop. Pa, my grandfather the barber, just laughed like he always did. He’d be charging rent to a lot of old men if he ever got started on that. The barbershop was a thriving business on Main Street in Richards, Texas. Main Street was the only paved street in Richards (Pop. 440), and Pa was the sole barber in the area. People drove from all over Grimes County to his out-of-the-way shop with one barber’s chair that was bought in the 1920s when he first opened. Waiting patrons and gossipy old men sat on two wooden benches.

Past the benches was a shoeshine stand that Pa used when somebody wanted shiny boots. Along the wall behind the barber’s chair were a long mirror and two shelves that held the glass display boxes. One of the boxes housed gleaming scissors, combs, and brushes for haircuts. The other held shaving mugs, razors, and Old Spice bottles for the shaves. Everything was spotless.

Pa was happy to see me. “Hey, sugar. You here for your shave?” he asked.

“I sure am, Barber Morris,” I replied in my most grownup customer voice. It was the summer after my second grade in school, and I loved to come to the barbershop. Sometimes I brought my play knife and sat on the porch outside the shop and whittled with the old men who lolled there for hours just talking and whittling. Other times, I had business with my grandfather.

Like today. Pa got out the little booster seat and put it in the barber’s chair so I could climb up on it. I was too small to sit in the chair without it.

“How about a haircut with your shave? That pretty blonde hair is getting too long for this summer heat,” he said.

“No, thanks, Pa. Mama always tells me when to get my hair cut,” I said. “Just a shave today.”

Old Man Tom Grissom nodded at this. “I sure wouldn’t be cutting that blonde hair without Selma knowing,” he said. “She’s mighty particular about things.”

“I appreciate your advice, Tom,” Pa said with a trace of annoyance. “But Sheila Rae and I are just having a conversation for fun. Nothing serious.”

Pa listened as Tom Grissom talked and talked and talked some more about delivering the mail that morning. Being the Richards rural-route carrier was hazardous, to hear him tell it: cows in the road to drive around, barking dogs chasing armadillos right in front of him. This was hard work, and then you had the heat! Why, he couldn’t keep his khaki uniform dry from all that sweat. Yes, sir, this was no job for the faint-hearted. And on and on.

Meanwhile, Pa had placed the thin white sheet over me and leaned the chair back just far enough to start to work. He lathered up the shaving cream in his mug with the brush and dabbed it on my face. I loved the smell of the shaving cream. He let that soak while he took the razor strop attached to the chair and swished it up and down slowly and methodically to get it just right. It didn’t matter to me that he was using the side without the blade. It made the same swishing noise.

Then he took the bladeless side of the razor and gave me the best shave ever. He was very careful to get every part of my face. He even pinched my nose so that he got the part between my mouth and nose just so. Pa was an artist with his razor and scissors. He put a warm wet white cotton laundered towel over my face and rubbed off the last of the shaving cream. It felt so clean. Finally, he took the Old Spice After-Shave and gave it a good shake, rubbed it on his hands, and then on my face and neck. Nothing beats the aroma of Old Spice.

Old Man Tom Grissom said, “Well, that ought to do you for a week or so, won’t it?”

“Yes,” I said. “Probably so. We’ll see.”

Pa gave me the worn yellow hand mirror that he gave to all his customers to inspect his handiwork. I studied my face thoughtfully.

“Well, how does it look to you?” he asked with a smile. “Time to pay up. That’ll be two bits for the shave. That’s with the favorite granddaughter discount.”

“Very good, Barber Morris. Much obliged.” I reached into my jeans pocket and brought out some play money coins and handed them to Pa.

Just about that time, Ma drove up and got out of her car. “George, what’s Sheila Rae doing in that chair?” she bristled.

Old Man Tom Grissom said, “Betha, Sheila Rae’s here for her shave.” Ma gave him a withering look and said, “Is your name George? Don’t you have any mail to deliver, or would that require removing yourself from that bench you warm every day?”

I got down from the barber’s chair and ran over to Ma and tried to reassure her that everything was all right. Ma looked at Pa and said this was just what she had been telling him the other night about encouraging me in all this foolishness.

“She shouldn’t be spending her summer hanging around this shop,” she said, looking accusingly at Pa, who said nothing.

“Ma, can I have a nickel to go get an ice cream cone at the drug store? Getting a shave makes me hungry.” Ma never said no to me, so I got my nickel and left. I walked across the street to Mr. McAfee’s drugstore and got my Blue Bell vanilla cone and headed home.

I saw Ma and Pa still in animated conversation at the shop.

Old Man Tom Grissom had gone home.

**********************

Deep in the Heart: A Memoir of Love and Longing was published in 2007 when I was 61 years old. Much has changed in the past 18 years, but I continue to smile when I read this story of the little girl growing up in the 1950s in the tiny town of Richards, Texas. I can see her now walking the block on a red dirt road from the house where she lived to Main Street, not in any hurry but not dawdling like she did some time, on her way to town. Summertime meant no school, looking for things to do during the day for the only child whose few playmates might not be around, so her mother let her go to town to be entertained by her grandparents. Her mother’s mother worked in the general store as a clerk, so Sheila Rae could stop there for a hug and maybe a nickel for a candy bar unless her grandmother had customers in the store, or she could walk past the general store and the post office to the next small building that housed the barbershop owned by her grandfather on her daddy’s side. Someone once said to my father, “Glenn, you have such a happy child. She’s always smiling,” to which my daddy replied, “Why shouldn’t she be happy? Nobody ever tells her no.” When I wrote this book in 2007, I’m sure I didn’t fully understand what he meant by that remark. Now that my wife and I have two granddaughters, I totally get it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.