Full disclosure: I am a card carrying member of FOSG (Fans of Savannah Guthrie) and joined the millions of Savannah’s admirers who have watched the painful unfolding of events in the abduction of her 84-year-old mother, Nancy Guthrie, from her home in Tucson, Arizona, on January 31, 2026. Updates on her disappearance are closely watched at our house.

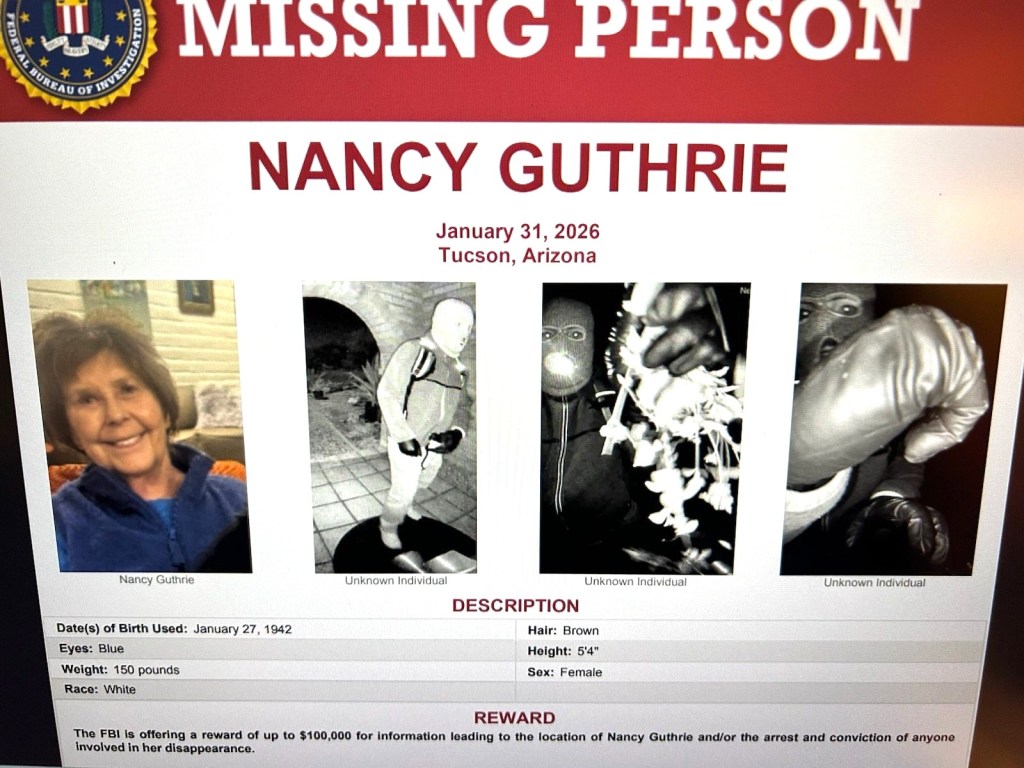

I visited the FBI Kidnappings and Missing Persons website Thursday morning and took a screenshot of an FBI poster for Guthrie posted that day:

DETAILS

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Phoenix Field Office and the Pima County Sheriff’s Department in Arizona are investigating the disappearance of Nancy Guthrie, last seen at her residence in the Catalina Foothills neighborhood of Tucson, Arizona, on the evening of January 31, 2026. She is considered to be a vulnerable adult who has difficulty walking, has a pacemaker, and needs daily medication for a heart condition.

************************

Bill Chappell at NPR interviewed experts for his article on the Guthrie case published February 13, 2026:

More than 500,000 people were reported missing in the U.S. last year, according to the Justice Department. But Tara Kennedy, media representative for the Doe Network, a volunteer group working to identify missing and unidentified persons, says high-profile kidnappings are rare.

“I can’t remember the last time I heard about a ransom case besides Guthrie,” says Kennedy, who has worked with the Doe Network since 2014. “I always associate them with different periods in American history, like the Lindbergh kidnapping, not someone’s mother from the Today show.”

***********************

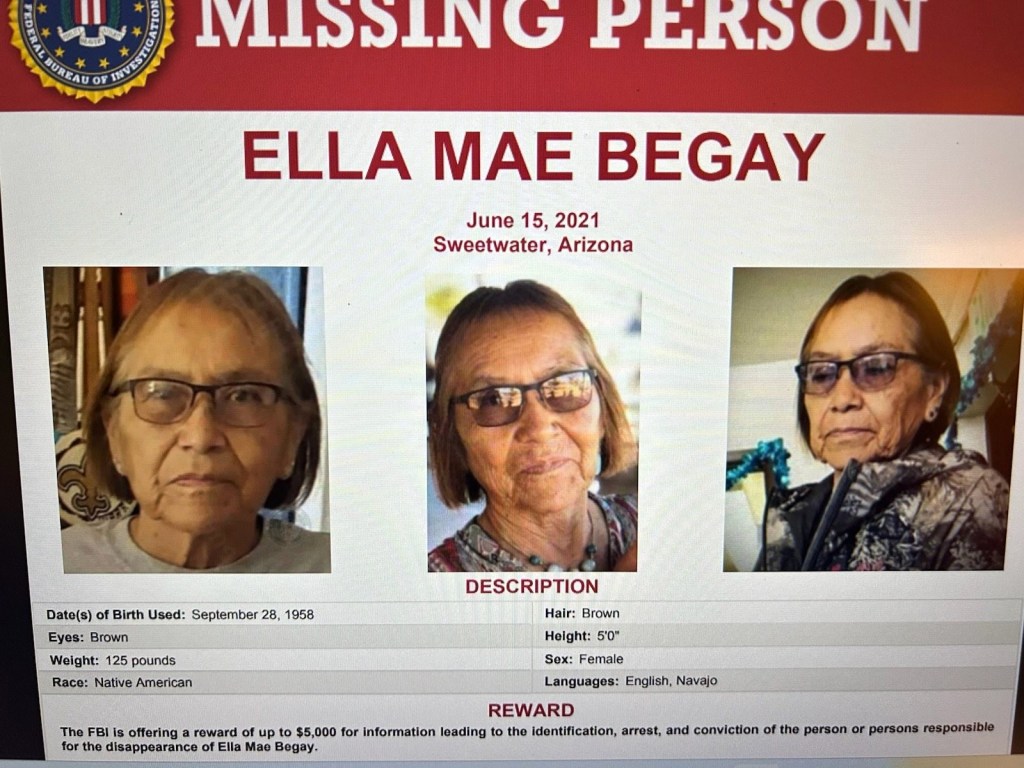

Black faces. Brown faces. Little girls. Little boys. Teenagers. Stats, stats, stats. White women. Brown women. Black women. The FBI Kidnappings and Missing Persons website was like a patchwork quilt of the American experience. One woman’s picture caught my attention especially – a Native woman, Ella Mae Begay, from Sweetwater, Arizona. How far was Sweetwater from Tucson, I wondered? 131 miles as the crow flies according to a map. How far was Begay from Guthrie? Much closer.

This is a screenshot of the Begay poster from the Kidnappings and Missing Persons FBI website – she was 61 years old when she was reported missing:

DETAILS

On June 15, 2021, Ella Mae Begay was reported missing from her residence near Sweetwater, Arizona, by family members. Early that morning, her vehicle, a Ford F-150, was seen leaving the residence. It was believed that the truck may have been driven toward Thoreau, New Mexico, and may have proceeded in the

direction of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Ella Mae’s vehicle was described as a 2005 Ford F-150, gray or silver in color, with a broken tailgate that would not close with Arizona license plate AFE7101.

*********************

Be still, and the earth will speak to you. (Navajo quote)

You must be logged in to post a comment.